The insane talent vortex at early Google

What happens when you give the smartest people an unlimited budget to solve impossible problems?

Google might be the closest answer we have to that hypothetical.

The tech giant today has over 180,000 employees, around half of them in Engineering. But what’s striking to me is how the most impactful technical breakthroughs, especially in their “scale-up” phase from 2000 to 2015, often came from just one or a few select individuals: The 5-person Gmail team, the PM rewriting Google Maps over the weekend, 4 days of pair programming to optimise the entire index, etc.

You could argue that nearly half of Google’s value today (~$2 trillion) can be directly attributed to the top 9 engineers throughout its history.

They are the Google Fellows:

Urs Hölzle architected Google’s internal cloud, turning servers from a cost centre into a significant competitive advantage. His early work on file systems, cluster scheduling, and networking carried over to their external cloud (GCP, today a ~$50B annual run rate business on its own).

If your team mandates peer code reviews or writes postmortems, you can thank Hölzle too. He introduced these practices at Google as employee #8. The engineering culture he set would be copied by a generation of Silicon Valley startups.

Luiz André Barroso practically invented the modern data centre as we know it. He co-authored "The Datacenter as a Computer" with Hölzle, which pushed for co-designing hardware, software, networking for efficiency and performance at scale. Barroso deeply appreciated what he calls the “obvious questions”—In his most-cited paper, he asked: “Shouldn’t servers use little energy when they’re doing little work?”

Amit Singhal became obsessed with informational retrieval after studying it under “the father of digital search” at Cornell. He rewrote the core search algorithm (expanding on the OG PageRank) in 2001 then led Google Search for the next 15 years.

R. V. Guha co-created the Resource Description Framework (RDF) and Really Simple Syndication (RSS), which set the standard for how data moves on the web. His work on Schema.org further organised the world’s information and helped Google index & serve more relevant results.

Ramakrishnan Srikant was one of the first to apply ML to improve ad systems (quality, targeting, prediction) and built their early internal ML infra. Search accounts for 58% of Alphabet’s total revenue (~$200B annual run rate), so even the tiniest optimisations that get the right ads to appear end up being insanely valuable.

Sebastian Thrun is a renowned researcher in AI, robotics, and autonomous systems. While at Stanford, he led the team that won the 2005 DARPA Grand Challenge for driverless cars. He later joined Google to found X, the moonshot factory that spawned Waymo (most recently valued at $45B).

Norm Jouppi is the chief architect behind Google’s Tensor Processing Unit (TPU), a specialised chip for running AI workloads (aka AI accelerator). Now in its 7th-generation, the home-grown TPU has been key to Google pushing the frontier on AI models vs. competitors that rely on scarce (& more expensive) Nvidia GPUs. His work paved the path for all the other hyperscalers now designing their own custom chips to meet the demand for AI.

The engineers profiled so far have been bonafide Google Fellows, or Level 10 on their internal ladder. Joining that rarefied group requires not only significantly shaping Google’s technical directions, but becoming the world’s leading experts in their fields.

But there’s yet one higher distinction—Senior Google Fellow (L11).

And in Google’s entire history there have only ever been two—Jeff Dean & Sanjay Ghemawat.

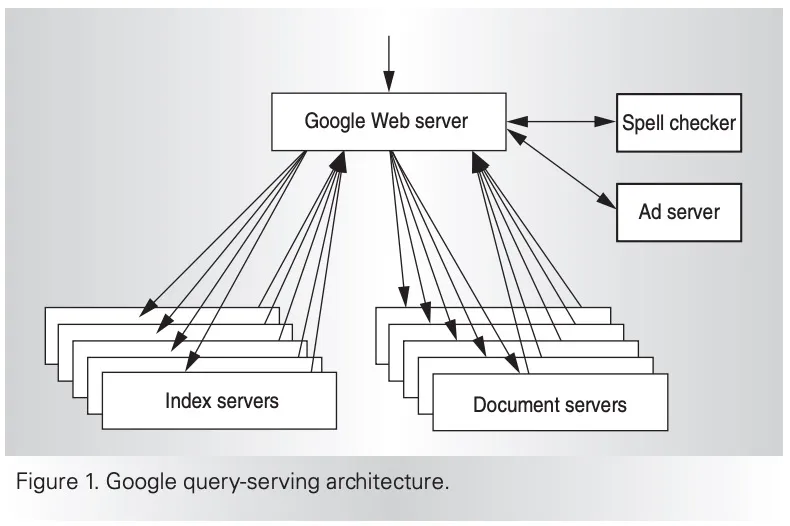

Jeff and Sanjay joined Google around the same time in 1999 and immediately made a splash, rewriting the original janky crawler and indexer many times over.

Their legendary pair programming sessions produced the core infra services that made Google “planet-scale”: Protobuf, Google File System (GFS), MapReduce, Bigtable, Spanner, (the list goes on)

Now in their 3rd decade at Google, through multiple major shifts in computing, they show no signs of slowing down. Currently leading AI efforts like TensorFlow/JAX, AlphaChip, model distillation, scaling test-time compute, etc.

Will we ever see talent density like early Google in another organisation? My intuition says no, or at least not for a very long time.

First, we have to keep in mind that Google had a near monopoly on this unique strain of “CompSci PhD-technical generalist-systems thinker” talent for a very long time. Microsoft sat in the antitrust regulatory sin bin for Google’s opening decade and completely missed the web. Apple had a design-centred culture, where engineers took a backseat. Facebook’s technical challenges didn’t become Google-scale or interesting enough for star programmers until ~2014. Amazon was more of a talent magnet “General Manager” types who are great at capital allocation and running P&Ls (e.g. Andy Jassy, Dan Rose). Nvidia wasn’t able to pay top dollar until this latest AI boom.

For a while, the “next Google” was supposed to be Facebook, then it was Uber, then Stripe. Now people say it’s OpenAI. Where the comparisons fall short is that Google became profitable in Year 3, whereas these “next Googles” were / are far more dependent on venture funding. Without the money printer that is the core Search Ads business, it becomes much harder to justify staffing expensive teams to work on green field ideas that might not pay off for a decade (self-driving, quantum, computational genomics, etc.).

Lastly, there are simply more and better opportunities for the best engineers today. If Bret Taylor stayed at Google his whole career, he probably would’ve made L10. But it was far more lucrative for him to leave, start a company, get acquired by Facebook, start another company, get acquired by Salesforce, and repeat. Same goes for researchers, like the Ilya Sutskevers and Chris Olahs of the world.

Coda

It was fun to dive into this history, watch some old talks, and ask LLMs a bunch of questions along the way.

The more you read about Google’s rich engineering history, the more you believe in the power of the individual contributor and the compounded effect of bringing the best people together.

Most successful tech companies are lucky to land just one engineer of this calibre for any amount of time. Generational companies might get a few every decade. The fact that Google recruited nine such people (& possibly more!) in part explains why they’ve been so good for so long.

With the right people in the room, a simple idea can go really far.

Notes

- The heavy lifting of this piece was done by Deep Research (Gemini 2.5 Pro). If you’re interested, you can see my initial prompt and the AI-generated report. How do you think it did?

- There are a number of people operating at a level that surely warrants being a Google Fellow, but aren’t. Demis Hassabis, Noam Shazeer, Oriol Vinyals, and Ian Goodfellow, to name a few. Perhaps it doesn’t count if you joined through an acquisition? I’m still not sure what the actual criteria are or who has the authority to decide. I’m curious if anyone reading this knows!

- Other possibilities are the unsung “second authors,” who do a lot of the breakthrough work but don’t get the recognition because they weren’t the DRI. Cliff Young, who was instrumental to early TPU designs and implemented systolic arrays, is one example.

Recommended reading

- Winters et al, Software Engineering at Google

- Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg, How Google Works

- James Somers, The Friendship That Made Google Huge

- Talks:

- Jeff Dean, Challenges in Building Large-Scale Information Retrieval Systems

- Luiz André Barroso, A Brief History of Warehouse-scale Computing

- Technical papers:

- MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters (2004)

- Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data (2006)

- Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database (2012)

- Ten Lessons From Three Generations Shaped Google’s TPUv4i (2021)

- Web Search for a Planet: The Google Cluster Architecture (2003)

- Misc:

- How Gmail Happened

- The time Bret Taylor rewrote Google Maps frontend

- Take a look at Sanjay’s elegant code, like his Go stream package implementation.